library(lubridate, warn.conflicts = FALSE)

my_time <- ymd_hm("2024-08-15 09:00", tz = "America/Chicago")

with_tz(my_time, "UTC")[1] "2024-08-15 14:00:00 UTC"In many cases, the easiest way to put some R code in production is with GitHub Actions (or GHA for short): since your code is already in Git, and on GitHub, it’s easy to use GitHub Actions. The main constraint here is that if you want to do it for free, your code needs to be public.

Only suitable for batch jobs, not interactive.

GHA are extremely powerful and flexible. My goal is not to demonstrate their full power, but to give you the most useful bits. I’ll point you to the docs so you can learn more if needed.

A few of my jobs you might be interested to read about:

https://github.com/hadley/available-work: scrapes an artist’s website and notifies me when new work is available.

https://github.com/hadley/houston-pollen: scrapes daily pollen data and aggregates it into a yearly parquet file.

https://github.com/hadley/cran-deadlines: turns CRAN deadline data into a Quarto dashboard.

To use GHA, you create a YAML file like .github/actions/{name}.yml. It defines when your job will run and what your job will do. By and large, you do not create a GitHub action from scratch by hand; you’ll typically copy from an nearby existing example and modify it as needed. (You might also try creating it with an LLM; but beware, debugging a GHA is frustrating.)

Here’s a simple example that runs an R script every time you push to GitHub.

name: run.yaml

on:

push:

branches: main

jobs:

run:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: r-lib/actions/setup-r@v2

- uses: r-lib/actions/setup-r-dependencies@v2

- run: Rscript index.RIf you’re ever confused by exactly what is going on in a GHA workflow, copying and pasting it into your favorite LLM engine and ask for an explanation.

The yaml has two main components: jobs defines what to do and on defines when to do it. You’ll also supply a name field.

As you might guess from the individual steps, GHA is quite low level. Here we have to first checkout our code, then install R, then install the R packages that our script needs, then run the script. We’ll go into more details of each component as we move through the chapter.

There are three names involved: the file name, a name within the yaml, and the job name. In most of the cases we’ll be seeing, there’s only one job, so we recommend this simple naming convention. If the filename is foo.yaml, then the action name should also be foo.yaml, and the job name should be foo.

The easiest way to get started is to use a template from https://github.com/r-lib/actions/tree/v2-branch/examples. And you can get that into your project with usethis::use_github_action().

Some basic vocabulary:

There are over 40 different ways to trigger a GHA to run, but fortunately there are only 4 that cover 90% of your needs:

schedule: run on a specific schedulepush: run when you push to GitHub.pull_request: run when you open or update a pull request.workflow_dispatch: run manually, on demand.The schedule event is useful when data is changing independently of your code (the most likely scenario).

on:

schedule:

# Every day at 5:30am and 5:30pm

- cron: '30 5,17 * * *'This format is a called the “cron spec” because it’s the specification used by the Linux cron utility (it’s named after the Greek chronos, which means time). It is organised into five fields representing minute, hour, day, month, and day of week.

Fortunately you don’t need to know anything about this format to use it effectively. You can either use https://crontab.guru/ or ask an LLM to generate a cron spec for you.

0 9 * * 5

0 0 * * *

I recommend that you always include a comment describing the schedule.

Whenever you create a cron spec to use on a shared computer (like on GitHub actions), I highly recommend specifying a random minute offset: sample(setdiff(0:59, seq(0, 60, by = 5)), 1). This is because humans tend to pick nice round numbers which means that a bunch of jobs are likely to be kicked off exactly on the hour etc, and are likely to be slow.

There are two challenges to be aware of with GHA:

The scheduled job will only run for 60 days after last commit to repo. That means if you want it to keep running indefinitely, your job will need to commit to the repo when something changes. We’ll cover that later.

There’s no way to pick a time zone: it’s always run in UTC time. That means, for example, there’s no way to actually run a report at 9am your time every day. You can use your offset from UTC, but in most places your offset from UTC is not constant because of daylight savings time.

You can also provide multiple cron specifications if you want something more complicated.

Useful to run every time your code changes:

on:

push:

branches: mainTypically, you only want this to run on your primary, or main branch1; if you want to it run on other branches you’ll create a pull request, the topic of the next section.

Also useful to run when others (or you) submit pull requests.

on:

pull_request:By default runs when the PR is opened and whenever it’s updated. It won’t run if there are merge conflicts.

We’ll mention this again later, but pull requests that come from forks don’t have access to secrets. (Otherwise anyone could provide a pull request to your repo and print your secrets.)

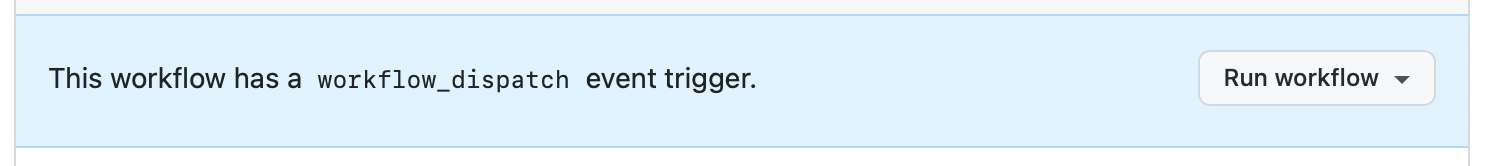

Finally, it’s useful to provide an escape hatch to manually run the job whenever you need it (for example, if it failed for some reason and you need to re-publish).

on:

workflow_dispatch:Once you add this, commit, and push it, you’ll see a new button on the actions page:

Most repos will have all four, looking something like this:

on:

schedule:

# Every day at 5:30am and 5:30pm

- cron: '30 5,17 * * *'

push:

branches: main

workflow_dispatch:

pull_request:Now that you’ve defined when your code will run, it’s time to define what it will actually do. There are two main parts to this: you first need to set up your computational environment and then define the individual steps to setup, run, and publish your content.

Pick which runner to use: we recommend ubuntu-latest. You definitely want to be running on Linux to improve your production skills, and in our experience for R jobs there’s no harm in opting to the latest stable version (and then that’s one less thing that you need to maintain on your jobs).

jobs:

jobname:

runs-on: ubuntu-latestDepending on how you publish your results you might also need some additional permissions. This block gives the Git client running on GHA the ability to do things other than just read from your existing repo.

permissions:

contents: writeWe’ll see some other examples later on.

Every job has to do three things:

So pretty much every job will start with these steps:

jobs:

jobname:

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: r-lib/actions/setup-r@v2

with:

use-public-rspm: true

- uses: r-lib/actions/setup-r-dependencies@v2setup-r-dependencies will automatically install Quarto if it is not already installed and the repo has one or more .qmd files. If for some reason you need to install it manually, you can do so with:

- name: Install Quarto

uses: quarto-dev/quarto-actions/install-quarto@v1These steps all use the uses field, which refers to a workflow step that someone else has written. You can find the documentation and more source code by going to the corresponding GitHub repo, e.g. https://github.com/actions/checkout or https://github.com/r-lib/actions.

The actions organization is maintained by the maintained by GitHub, and the r-lib organization in maintained by the tidyverse team. It’s important to think about the maintenance of these actions because they can run arbitrary code on your repo. While I’ll show you how to minimize the scope of any secrets you share, you should carefully consider the pros and cons of using an action from an unknown author.

Now that you’ve checked your code and installed everything it needs to run, it’s time to actually run it! Now we’re going to switch from use to run. Here are the three most common jobs you’re likely to see:

- name: Run an .R file

run: Rscript scrape.R

- name: Render a .Rmd file

shell: Rscript {0}

run: rmarkdown::render("myfile.Rmd")

- name: Render a directory of .qmd files

run: quarto render(Something about tests and about not deploying unless the tests pass)

It doesn’t matter how much work you’ve done unless you’ve got some way to share it. There are two main ways to publish your results from GHA:

Commit the results back to the main branch. This is particularly useful for data engineering jobs where you want to save data in the repo itself.

Publish the results to GitHub Pages.

Depending on what publication means for you, you will want to consider if every event trigger should publish. For example, you probably don’t want pull requests to cause publication to happen, but you do want it to run and test your code.

if: github.event.schedule | github.event.workflow_dispatchGit itself has no concept of a primary or default branch, but every Git repo on GitHub does. The default branch is where code ends up, and using a default branch considerably simplifies most workflows. However, it’s not something that’s baked into Git itself.↩︎